BBC

BBCStacey Dooley: Why I followed four homeless teens for nine months

'It’s hard being homeless at any age but at 16 years old? I can’t even imagine.'

“Being out there… it’s not nice,” says Josh, 18*, as he queues for a bed in a homeless shelter in Blackpool.

“You have to guard everything when you’re sleeping. You hide your shoes in your sleeping bag, sleep on your bag, hide your phone down your pants. Druggies have tried countless times to nick my stuff. You have to tell them to get out of your face – if you don’t, they’ll just take it. They’ll walk over you.”

Josh, who once trained to be a mechanic, moved to Blackpool with his mum, brothers and sisters in 2016, when he was 16, but became homeless after his mum told him there wasn’t “enough room” for him at home. The next day, Josh went to a shelter, but his situation didn’t seem real until a few days later, when he realised he was actually on the street.

New research by Centrepoint, a charity which supports young people, estimates that 103,000 young people were homeless or at risk of homelessness in the UK between 2017 and 2018. Josh’s experience is one of several stories that Stacey Dooley follows for nine months in her latest BBC documentary for Children In Need: The Young and Homeless.

BBC

BBC“It’s hard being homeless at any age, but at 16 years old? I can’t even imagine,” says Stacey. “When you’re a homeless teen, how do you build a future, or have any sort of life?”

Visiting Streetlife, a local charity that provides shelter and support to Blackpool’s young homeless people and is supported by Children in Need, Stacey is told that with only a handful of emergency beds available, they operate a “first come, first served” service each night for young people with nowhere to sleep. First-timers and under-18s always get in and are offered a meal. But for a teenager like Josh who is over 18 and, at one point, was working late nights for a pizza chain, it often means missing the chance of a bed, and having to get his head down in a doorway.

“It’s utter madness,” says Stacey, “that organisations who’ve only got eight beds are handing him a sleeping bag and wishing him the best of luck.”

BBC

BBCIn the documentary, Stacey swaps her room at a B&B with a homeless girl staying at Streetlife, in order to get a glimpse into what it’s really like when you don’t know where you’re sleeping from one night to the next. “This place is such a safety net for these kids,” says Stacey. “Without it, they’d be much more vulnerable.”

The next morning, at breakfast, Stacey discusses the stereotype of homelessness going hand-in-hand with drug addiction. “That’s the assumption – that all homeless people do drugs,” says one guy, who plans to spend his day begging for money to buy food and water. “But not all of us do.”

Evidence suggests that a breakdown in family relationships is the main cause of youth homelessness – something Rachel Day, a support worker for under-18s, agrees with. Working with over 400 people aged between 16 and 18 each year, she says some of these teens are known as the 'hidden' homeless. “They haven’t got a fixed address, they’re not living with parents, or they’re sleeping on sofas. They might not see it as being homeless. They might just see it as living, getting by.”

BBC

BBCIt means the real number of homeless young people could be much higher, as thousands go under the radar. And, as Stacey discovers, “if you’re part of the so-called hidden homeless, you don’t get help, so these teens face their struggles alone”.

Teenagers like Cat, 19, and Shelby, 18, who are friends from Manchester. When Stacey first meets them in the documentary, the girls tell her they walk the streets at night as, like Josh, they’ll “get robbed” if they go to sleep. “It’s every man for themselves around here,” says Shelby.

“I’ve been homeless since February,” says Cat, who joins the one in five teenagers who have sofa surfed in the last 12 months.

BBC

BBC“It seems to me that these kids are being let down,” suggests Stacey, after Cat says that the homeless people she knows avoid staying in hostels because of their reputation for being "dirty' and 'full of druggies'. “You’ve got to share a floor with eight other people,” adds another guy, who also used to be homeless. “You don’t know what sort of characters they are – a lot are on bail or just out of jail.” That said, some people might be just down on their luck, or there for circumstantial reasons beyond their control.

Last year, government figures from England and Wales revealed that 90 kids are taken into care each day, but a previous study from Action for Children suggests that some young people might not be getting the emotional support to become fully independent.

Shelby is someone who became homeless as a result of leaving care. “I was shocked,” she says, remembering the first night she was taken into care by social services, aged 14. “It was meant to be a respite, but for some reason they kept me in longer. I had a lot of hatred towards my mum for doing it, but now I’m older, I understand why. She’s proud I’m not just sitting ‘being homeless’. I’m trying to get a house and sort my life out.”

BBC

BBCJosh tells Stacey that in the past he has given his bed at a shelter to homeless girls who didn’t get one, as he didn’t like the idea of them being outside overnight. “You don’t let that happen,” he says.

Fearing for Cat and Shelby’s safety, Stacey asks what’s the scariest part of being homeless for an 18-year-old girl. “There’s quite a lot of crime,” says Shelby. “Girls are getting groomed on the streets. There’s an art to grooming where they can twist your mind and make you feel like it’s your fault. I tend to stay away from the bad people because I’ve been through stuff before, so I can spot things.”

As well as the risk of grooming, theft and drug abuse, having no place to call home also hits your mental health. During their months of being filmed for the BBC, Cat and her boyfriend were given a tent by a charity. “Living in a tent makes you depressed,” she says, giving the grim tour of her surroundings under a railway arch. “You start to not look after yourself because you’ve not got your own stuff, or your own place. You can’t even wash your hands, you haven’t got a toilet – it’s so stressful. But some [homeless] people don’t care.”

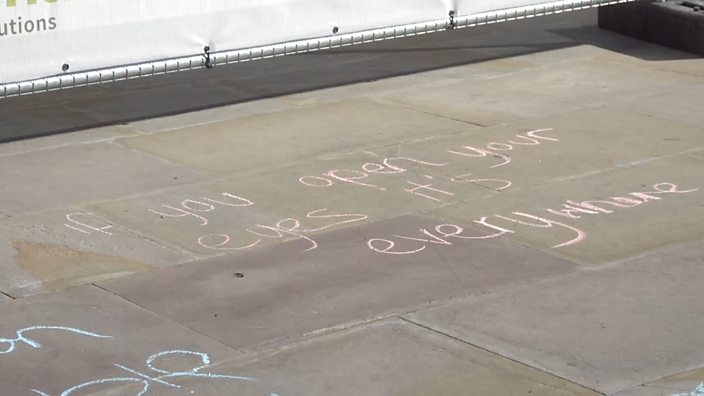

A homeless person under-18 is treated as a priority by housing teams, but once they turn 18, the age they’re legally classed as an adult, that can change, which is why both Cat and Shelby have protested about what they see as unfair treatment. In the documentary, they write the words, “If you open your eyes, it’s everywhere", in chalk outside a housing convention in Manchester’s city centre, referring to homelessness.

BBC

BBCA new law – The Homelessness Reduction Act – came into force in April, meaning support should be available to every young person who’s homeless. But CentrePoint has warned that an extra £10m would be needed in order to cover the number of 16-24 year-olds who ask for help.

“When I see [some of] these youngsters on the streets… they’re feral; they’re wild,” says Stacey. “People on the outside might say ‘that’s [the life] they want’, [but] in many ways, no one has invested time in them or encouraged them to be the best versions of themselves. That’s why organisations, NGOs and charities are so necessary and important.”

And some are already making a difference, including Lifeshare – a voluntary organisation in Manchester which, at the time of filming, said they helped 130 people in the last four months.

Their twice-a-week drop-in service offers the city’s young homeless (including Cat and Shelby) a shower, food and help in finding a permanent place to live.

BBC

BBC“The staff have walked the walk here,” says resettlement worker Susan Grumbridge, relating personally to the practical and psychological frustrations behind wanting to get off the streets and build a life. “People can be intimidating, but that aggression is not aimed at us - that’s aimed at society and what it’s doing to them.”

Meeting visitors at Lifeshare who have and haven’t found accommodation, Stacey makes a point that “not all these kids are angels”. But she’s also aware of their circumstances that led them to where they are. “You’ve got to bear in mind what they’ve been through. Some have been in care or haven’t felt loved or supported for years.”

“We just want stability,” says Shelby. “A house to call our own instead of just being lost.”

Last year, research found 13% of young people who presented themselves as homeless were accepted as statutorily homeless and therefore housed by their councils. “The process is long,” Josh tells Stacey. “I haven’t got a local connection with Blackpool, which makes it harder as you need to be here three out of five years.” His only option involves raising money and bonds for help with private rented accommodation. “I’m low priority and because I’m working, I’m even worse off.”

Thinking back to her own worries at 18, Stacey says it just doesn’t compare. “I was working at Luton airport and all my money went on buying tops and going out. I had no fears, no responsibilities. Josh has to look after himself because he’s got no one else.”

Of course, feeling that you have some kind of family around you that you can rely on is important, especially when you’re growing up. With councils facing seemingly endless cuts, Stacey says “a brilliant idea” is spreading fast: host families – volunteers providing family-like environments to homeless young people.

BBC

BBC“We know children thrive better when they’re in a family home,” explains youth housing officer Charlie Hazell-Jackson. “Host families give someone who’s having a tough time somewhere to stay.”

But charities that run these schemes are always desperate to find more willing people to take part.

Someone who’s flourished from the initiative is Millie, 16, from Devon. “I moved out when I was 14,” she says. “Home life wasn’t very good. There were a lot of issues growing up and it wasn’t a nice environment to live in. There was a point I couldn’t take it anymore. My GCSEs were coming up and I knew what I wanted in life.”

Millie's teacher referred her to Encompass South West, which uses Children in Need funding to provide The Junction project, which supports young people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness in rural communities. Here, she met Charlie, who became her housing officer and helped her find a local host family willing to take her in. “It was really nice to know there was somewhere else I could go, especially somewhere that was so homely,” says Millie, who is now thriving and hoping to study medicine at university.

BBC

BBCBut the stress of being homeless still takes its toll. "As a teenager, you’re already going through so many changes within yourself… your emotions feel so heightened, so to have all that stress on top of what you’re going through already, it really does affect you. I think everybody needs a home or a safe place to be, otherwise you can’t really move on with your life.”

Reflecting on her time with these teens at the end of filming, Stacey says she’s delighted that those she followed were in better positions, including Josh, who had two jobs on the go and had finally sorted a permanent place to live.

Cat also hopes to leave her homeless days behind soon, and by the end of the documentary was staying at an all-female hostel, which she thinks is the “best method” for someone like her. “We don’t get enough information, because if I knew there were places like these before, I’d have got help a long time ago, instead of trying to avoid the system,” she says.

BBC

BBCBut with rising numbers, 'the system' still has a long way to go, and Stacey admits to underestimating the enormity of the situation. “We can’t forget that there are so many young people who are homeless – and unbelievably vulnerable,” she says, before calling for more advocates like Rachel, Susan and Charlie who believe in them.

“How can we expect them [young homeless people] to become fully independent adults if we haven’t nurtured them? It's painfully predictable: if it starts now and we don’t intervene, that will be them for 20 or 30 years – it’s our responsibility to look after them.”

*all ages correct at time of filming

BBC Children In Need supports young people experiencing homelessness all over the UK. If you need advice, visit bbc.co.uk/pudsey

Watch Stacey Dooley: The Young And Homeless on BBC One on Tuesday 13 November at 10.45pm and on BBC iPlayer